Editor’s Note: This post was originally published by Jason Kaehler, CEO at Asylum Labs. With decades of experience making games, Jason knows the importance of having a good development process and finding the proper product/market fit.

One thing I have noted after making games for 25+ years is that good process is critical. It is perhaps noteworthy that the further into a development cycle we go, the more ‘formal’ and ‘structured’ the process is. For example, post-alpha with emphasis on bug fixing is very tight, whereas ‘prototypes’ and ‘brainstorming’ are often more loose. But what about the most important question of all, “What game SHOULD we make?”. In this article, I share our process here at Asylum Labs.

If the goal is to create a sustainable business (and not just a hobby), you will need to think carefully about product/market fit. I have written about this previously, and I also recommend you check out my friend Mathew Emery’s articles on the subject here; HERE

Our approach at Asylum Labs :

Phase 1 – Determine game genre & high-level design

Phase 2 – Validate Theme/Art choice – Focus Test

Phase 3 – Prototype innovation

Phase 4 – validate prototypes for fun – Play Test

Phase 5 – Formal game design

Phase 1 – Determine game genre & high-level design

The goal of this phase is to conclude with a high-level ‘1-page’ overview of the game you propose to develop. You will want to list the genre, sub-genre (where appropriate), art style, and systems/mechanics. Feel free to reference existing products for solutions where you will not be innovating (more on that later). We need a process that will give us the optimal approach to achieving this Phase 1 deliverable.

There are essentially three Pillars to this decision.

- Market Need – what is the data telling us about targets of opportunity

- Passion – what do people on the team WANT to do

- Experience – what is the relevant experience of the team?

Pillar 1: Market Need

Market Need is fundamentally understanding where there is an opportunity for a new game to either a) steal market share or b) grow the category. To do this, we must first have a taxonomy of game genres, sub-genres, and sales data to support our investigations. I like the game categorization at GameRefinery (App Annie, SensorTower, and Apptopia are also good; more on multiple data sources later).

From there, I like to break Market Need into 3 sub-components:

- Optimal Growth Curve

- Competitive Analysis

- Player Reviews / Forums / Discord feedback

Optimal Growth Curve

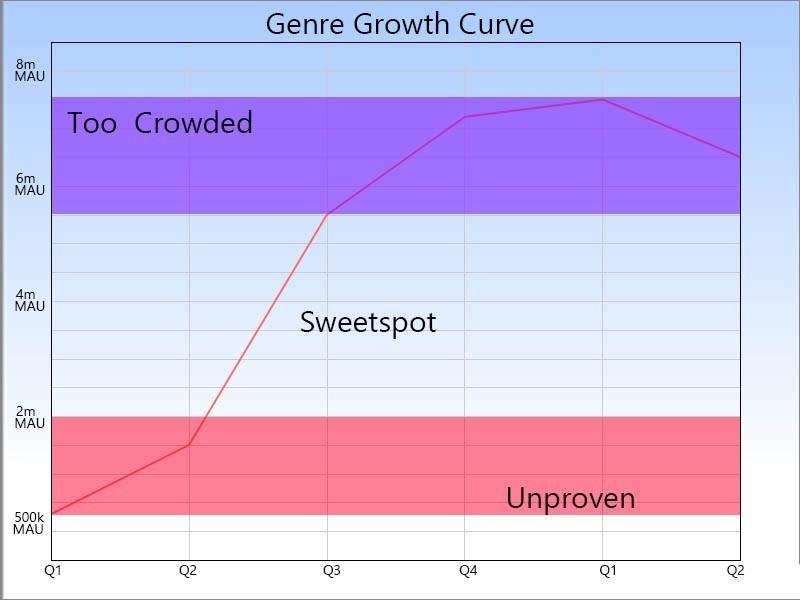

I’ve mentioned in previous articles how to ‘snapshot’ identify opportunity based on segment metrics (MAU/gross revenue) and look at how crowded the space is. Here I’d like to suggest a companion approach that looks at temporal context.

Armed with your data you are now in a position to look at genres/sub-genres over time. Video games are an extremely competitive and copy-cat industry and whenever something gets ‘hot’ there will be an inevitable gold rush into the space. The trick is to find a category that is big enough to be ‘proven’ but not so big that it’s crowded by the mega-corporations throwing millions at marketing. This is sometimes called “red waters / blue waters’ (‘red waters’ means blood in the water, meaning crowded category).

You are looking for the ‘front crest’ of the wave (a phenomenon also seen in real estate, where the process of gentrification has a ‘front crest’ also). Keep in mind your development time, short-term fluctuations, and long-term cyclical trends. This method is ideally targeted at identifying emerging genres.

Note: This graph shows MAU only but you will want to look at revenue also, ARPMAU. Generally, (for popular genres), ARPDAU’s are fairly well ‘known’ and stable for entire categories, and you will want to dig into the #s of specific competitors also.

Finally, there is one other consideration, which is ‘How big of a game do you NEED’? We all want a top 20 game, but it may be more realistic to target top 150, or even top 250.

In practical terms this means more opportunities open up (genre-wise) because these categories will be more ‘blue waters’ almost by definition. If you have a small studio of 10 people, maybe you don’t NEED $15m/month, and could be quite happy with $5m/mo.

With this approach, you can often find games/categories where deficiencies in current offerings are more easily identified as there is less competition the genre has more room to improve.

There are a couple of challenges with this Pillar. The first relates to multiple data sources. Ideally, you will not rely on one source for your analysis but work with an aggregate of information. Determining the relative validity of various sources is a challenge, as are the problems associated with a categorization. How many genres ARE there? How do you handle sub-genres? What if your game doesn’t fit neatly into the data-source’s genre definition? What if you disagree with the data source’s categorization?

Another challenge is that we are seeing a strong trend in the last few years of ‘hybridization’ which further complicates the issue of taxonomy. One solution is to simply map metrics from the top 5 competitors and create your own ‘sub-genre’ and derive your own metrics for that category etc. This can be time-consuming but is really the only option if you are working on something strongly innovative yet based on real-world data. Ideally (perhaps someday) we would have a standard template across our industry to facilitate this kind of analysis.

Pillar 2: Passion

Probably self-explanatory but I see many teams putting too much or too little emphasis on this component. Making games is REALLY HARD, and having something the team feels very passionate about will both help folks during ‘the grind’ and encourage them to do the best work of their careers. On the other side, individual team members may be creating games where they are NOT the target audience and that passion can be a bit harder to divine. Beyond the project selection phase, try to create a culture where passion is both nurtured and rewarded.

Pillar 3: Experience

What is the actual experience of team members (both individually and as a company) regarding games shipped? This is important because for a few reasons.

- There is a linear relationship between the Delta of NewGame / OldGame and Risk. Put another way, a sequel with just better graphics is MUCH less risky than going from a 2D Puzzle game to a 3rd person action adventure. This doesn’t mean you can’t make big leaps, but recognize this reality and plan accordingly.

- Experience directly affects the time/budget. If you have specific domain expertise, the development will go MUCH faster. R&D, training, onboarding are all incredibly time-consuming and expensive efforts.

- Beyond the dev cycle, experience in UA/marketing particular game genres may come with brand-relationships and partnerships that would provide unique value.

- Relevant life experience outside games? It may be that there are people on your team who have incredible insights into ‘the real world’ that could differentiate you from the competition. These folks tend to be a bit older and have a bit more life experience (but not always).

We are almost done with Phase 1, there is just one more step:

At this point, write-up your ‘1-sheet’ overview of the game. This doc will include every feature (bullet-point only), USP/innovation vectors (I have previously written about optimal % of innovation), Theme and art style, target demographic, platforms, and (rough) dev budget/schedule. This document can then serve as a hard ‘gate’ for all stakeholders to buy off before moving forward.

One thought experiment I find useful; imagine you are asking a top video game guru with extreme business intelligence for the money to make this game. They ask “why should I give you the funds” and you need a ROCK SOLID answer. Even if you will self-publish, going through this exercise can help to clarify internal thinking/discussions and design. (I may write a future post on pitching to publishers).

Phase 2 – Validate Theme/Art choice – Focus Test

Armed with your genre/sub-genre selection, here we want a process to determine the presentation components (as distinguished from the game design) for our game. One popular approach is the traditional Focus Test methodology; the simplest is setting up something like SurveyMonkey and getting as many people as possible to participate.

Much can be said about running focus groups, (perhaps future article!) but the main things to consider are:

- What answer do you want? Consider both qualitative and quantitative questions

- WHO will you get to participate? Ideally, they will be majority target audience for game

- Statistically valid – you will want a large enough data sample and use proper statistical analysis (ANOVA etc.)

Before getting into Theme & Art Direction questions, you will want some generic ‘profile’ information from the respondents. Age, Gender, Country, Income bracket, etc. Determining if they play games (and if they spend on them) in your chosen genre is also critical. A proper treatment of Focus Testing is beyond the scope of this write-up.

Theme vs. Art Direction

The theme is not art. A Theme is the meta-structure that informs the entire game and places it within a larger context (either through reference to other games or real-world concepts). You want a Theme that has strong ‘cultural resonance’. This is why some intellectual property (IP) can charge so much to license; instant cultural resonance. Even very abstract games like Geometry Wars have a cultural context regarding the long tradition of geometric games. It’s worth mentioning that in some games, music is a huge part of the Theme.

I recommend testing Theme concepts independently from Art Direction and WITHOUT visuals. For example, you might be considering a Match3 game but can’t decide between Themes of Pirates, Sci-Fiction, or Candy. Perhaps your survey would present a similar game and ask which Theme is most interesting to the respondent.

The game’s title could also be included, (ex. Pirate Odyssey, Space Friends, or Candy Treasures). This extra bit of color/info will help respondents to learn a tad bit more about the product. Of course, you will need to brainstorm your ‘best name’ for each of the Themes for this to be meaningful. Once a Theme is decided (post Focus Test), doing another separate Focus Test on just the name can be quite valuable also.

Art Direction

Art Direction is simply the ‘look of the game’. In the final analysis, this encompasses every visual element in the product and serves to provide an overall cohesion to the game. The purpose of focus-testing the art is to determine which direction may be optimally appealing for a given design/Theme/audience. To illustrate how Art Direction differs from Theme, consider the following images:

The Theme is obviously “Alice in Wonderland” however each illustration ‘feels’ very different and would likely appeal to a different audience.

For each theme, you will want at least (1) mock screenshot, (1) main character (if appropriate), and (1) logo/icon. Multiple screenshots may be necessary depending on the game.

If you are testing both Theme and Art Direction, you will want each of those elements for each Theme. I have seen companies try to save time/money by doing Theme A – Art Style 1, Theme B – Art Style 2, etc., and while useful, this is not a true ‘apples-to-apples’ comparison and therefore may bias respondents in unhelpful ways. The best practice is to test Theme and Art separately (can be part of the same Survey/respondents pool but just de-couple them). So Theme A – Art Style 1, Art Style 2, Art Style 3; Theme B Art Style 1….etc.

Phase 3 – Prototype innovation

Most games are similar to something else and choose to innovate along one or multiple vectors. While ‘innovation’ is a broad category, for this Phase we are concerned with gameplay (and/or) monetization/economy design. The idea here is that you want to prove to yourself that the shiny new solution is great/fun/rewarding etc. and will outperform other ‘off-the-shelf’ solutions used by the competition. If it’s easier, go ahead and do ‘stand-alone’ prototypes, just focused on the specific feature you are interested in. The sooner you can validate or reject these ideas the better.

Phase 4 – Validate prototypes for fun – Play Testing

Time to playtest that awesome new innovation you just prototyped! I recommend doing this in two stages:

Stage 1: Here is where we ‘eat our own dogfood’ (or dogfooding). Test within the team/studio first. Grab unlikely folks from HR, Accounting, and Marketing. Watch them play and note observations. Instrumenting your prototype with even crude core analytics can be invaluable at this stage. If you make the testing ‘fun’ (maybe during Friday afternoon with drinks/snacks) you will create a more casual atmosphere that facilitates candor.

Iterate on the prototype if necessary.

Stage 2: Go outside the company and get ‘regular people’ to test it. Depending on the complexity, they may need a bit of ‘setup’ as to what they are being expected to do, and what you want to know from them upfront. Try to target about ~80% in your target demographic minimum.

After this, you can sit down and ask yourself: Is it working well? Is it fun? Do people prefer it to ‘what the other guys do’?

If these prototypes are not performing well, consider going back and making changes based on feedback. If your choice of game genre (in the beginning) was dependent on you innovating in a key sector, and you have NOT proven you are successful, consider a completely different approach or even a different game.

Phase 5 – Formal game design

Finally, you are ready to write a first draft of the GDD (Game Design Doc). This will be a ‘living’ document and as such you will want to create something with lots of internal hyperlinks so it can be maintained easily.

We all hate giant GDDs nobody ever reads, however, there is great value in having a single resource everyone can commit to and reference during production; esp. before art & engineering get involved. There is an optimal amount of documentation you should target for your team, company culture, and project needs. Often it is a good idea to consult your Art & Tech Directors to ask what areas of the design they are most concerned with from a documentation perspective.

Congrats, you are now ready to START! As with most businesses, time is money. The extent (or scope) you put into each Phase will vary greatly depending on the studio, corporate culture and product envisioned. What is clear after decades in the industry is that a good pre-production process pays dividends during development.

Thanks for reading! If you found this interesting, useful, or just plain wrong, don’t hesitate to reach out to Jason at j.kaehler@asylumlabsinc.com. For more articles like this one, follow Jason on LinkedIn. Company: www.asylumlabsinc.com | Personal website: www.kaehlerplanet.com